After 2 years of petrol-like odours and serious health concerns the problems associated with Southall gasworks redevelopment continue. Would a change in how we monitor air quality at brownfield sites help? Dr Ian Mudway Senior Lecturer at Imperial College’s School of Public Health strongly agrees and he along with PhD student, Holly Walder, are setting out to change the way we assess air quality around brownfield sites.

It helps to understand the background of the former Southall gasworks, now the Southall Green Quarter development. From one perspective, it is one of the most ambitious brownfield developments underway in the UK. At 88-acres the redevelopment will create 3,750 homes and up to 500,000 square feet of commercial space, which is conveniently located by Southall Station on the Elizabeth Line, giving easy sustainable access from Reading to Brentford and south to Heathrow Airport. It’s also next to an extensive Victorian estate, primary and secondary schools, so development into a new residential estate will bring a piece of underused brownfield land back into productive use.

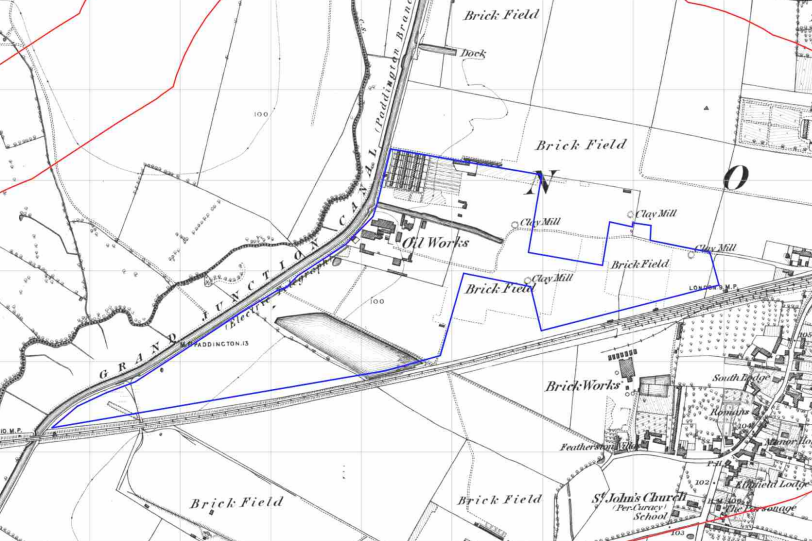

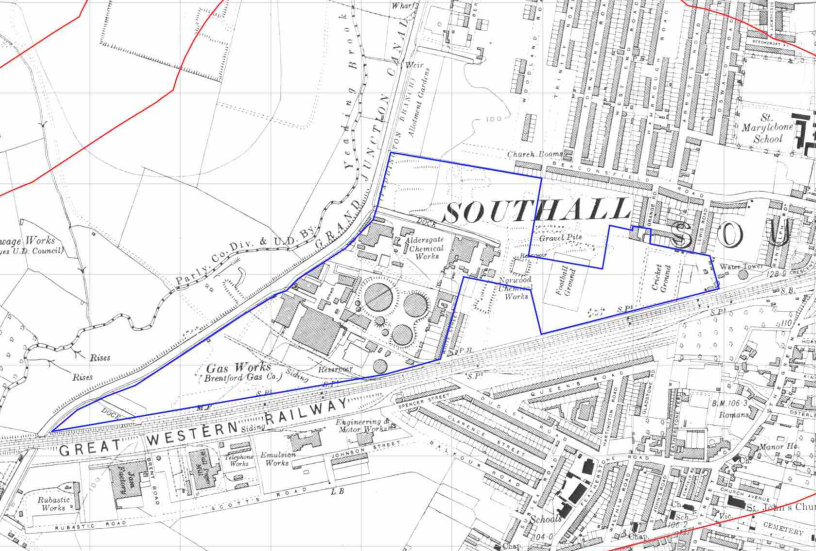

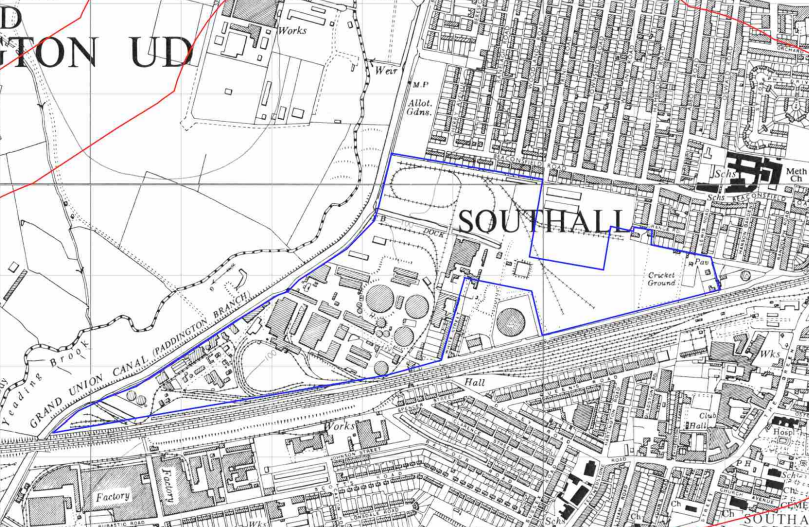

Extracts of mapping show the extensive industrial history of the site:

1868 1:10,560 scale

1913 1:10,560 scale

1913 1:10,560 scale

© Crown copyright and database rights 2018 Ordnance Survey 100035207

From a local residents’ perspective, the development is less desirable. Ealing Council originally refused the planning application, later overturned by the then Mayor of London, Boris Johnson using special powers to approve the project. With work starting in 2017 the development disruption has been present in the local community for 6 years with the first Phases now coming to market.

The remediation

In line with national sustainability policy, Berkeley Group agreed a remediation strategy that included cleaning the soil on site by creating a ‘soil hospital’. This consisted of stockpiles of soil to allow hydrocarbons to evaporate or biodegrade to acceptable levels for reuse on site. This has multiple sustainability benefits as it prevents unnecessary transport of hazardous materials through the London roads to landfill and transport of suitable imported materials to replace them in the other direction. There are fuel savings and reduced air pollution as well as the reduced safety risk of transporting contaminated materials through residential streets in large lorries.

The ‘soil hospital’ was located in the south west corner as far from the schools as possible. The developer made provision for air quality monitoring using current air quality standards. These standards are based on monitoring indicator compounds and public health guidance concentrations will have a variety of different assumptions in them to determine what is acceptable.

Aerial imagery 1999 – pre redevelopment

Aerial imagery 2019 – during redevelopment with soil hospital in the south west

Long term health impacts?

Since the start of the development local residents have had long term concerns about their health. When works started in 2017, 50 households started reporting breathing difficulties and the onset and worsening of asthma. Other conditions included eye irritation, irregular heartbeats, migraines, skin rashes, chest infections, nausea, dizziness, memory problems and a sensation of “internal burning”. Some said they only felt well when they left the Southall area.

By 2019, after some years of experiencing symptoms, local residents formed a campaign group, led by Jon Sidhu KC, who grew up in Southall. Their aim being to mount a case based on the tort of nuisance in response to what he calls “the abject failure of Berkeley to adequately respond to legitimate grievances.”

In 2023 the reports of ill health continued, despite the closure of the ‘soil hospital’.

Response

The response to these complaints resulted in involvement from the Public Health team from Ealing and the Public Health England (now the more alarmingly named UK Health Security Agency -UKHSA). The result being that the developer agreed to increased air quality monitoring.

The PHE air quality assessments reports from 2018 to 2020 present an interesting set of conclusions. It identified that some compounds, such as naphthalene and benzene, were intermittently above the chosen guidelines. Whilst naphthalene has the potential for an unpleasant mothball odour PHE’s overarching conclusion was that exceedances were unlikely to cause acute or short term health effects at the site boundary, with further dilution expected the further one travels from the boundary. With the closure of the soil hospital 2019 the VOC concentrations in the air dropped further. What the PHE does draw out is the impact of the unpleasant odour during ongoing development that may be triggering the reported health effects.

A new approach

So at the site there is an impasse. The residents are experiencing poor health which they attribute to the development, but the regulator (UKHSA) does not indicate that the air quality is the cause. What should the next steps be? This is where Dr Mudway steps in. His background is in air quality and he is part of the Health Protection Unit which is a partnership between the UKHSA and Imperial College, London. An area of current research is the impact of brownfield development on the health of the surrounding public. This is complex research including assessments of undeveloped brownfield sites, sites under redevelopment and post development sites. With every site having a unique context and a combination of contaminant sources, the aim is to identify how to fingerprint the individual sources so they can be individually assessed and managed.

The breakthrough in this research, which is being trialled at Southall, is a new method of sampling. Dr Mudway and his colleagues have designed a cheap, passive, air quality monitor – about the diameter of a golf ball. The intention is that this will enable samplers to be deployed in large numbers to improve the level of spatial detail. Further chemical detail is added as the analysis is by mass-spectrometer which will enable a full range of chemicals to be detected, not just compound specific as currently. The monitor is also wearable giving the best possible reflection of personal exposure. The aspiration is that the technology will be cheap and easy to use, enabling a more complete understanding of potential exposure routes to be understood. It does not take much to see that this could be applied to understanding not just brownfield locations, but other emission sources too.

The new technology is being tested at Southall to see how it can pick out the various local emissions sources. The site is well placed as there are multiple sources going beyond the gasworks redevelopment to include traffic, railway and asphalt works. The work has just started with ambient and personal monitors and will be running over the summer into next year. The local community will be updated with findings and the project due to be complete in May 2024.

Dr Mudway’s hope is that it will open up a wider conversation about how we monitor and manage air emissions. He explained that ‘low level long term exposure to non toxic levels of compounds over the long term by standard criteria actually have the potential to cause quite a lot of harm over the long term’ and these devices could provide the necessary information to re-evaluate what should be considered acceptable. This is especially relevant now where infrastructure developments can cause generational disruption to their local communities due to the long delivery programmes.

As with all good science more questions come to the fore and he has found this with this research. The team has had to work hard to win the support of local people as the problem has been long running. He identifies a confounding factor in ‘Big infrastructure projects that are so divisive are generally being rolled out over relatively disadvantaged communities who already feel that they have no significant agency and they feel absolutely steamrollered. So there is a secondary mental health impact on those communities.’ In other words the act of engaging to build trust and move from the more adversarial approach could significantly reduce stress and anxiety and, therefore, potentially the health impact of a development on the local community. It is an area he is considering for further research.

For more information:

Our Insights data packs and mapping can help environmental consultants and other land quality experts identify the potential sources of contamination on site – whether it is remaining unchanged or whether you are delivering an Environmental Impact Assessment or remediation strategy for a development.

Commercial Property Lawyers also need to be fully aware of the extent of potential ground contamination and how this could impact remediation costs and site viability for their client. Our Groundsure Review desktop report provides a comprehensive, consultant-backed professional opinion on the potential risks present on site ahead of completion.

For further information contact us on 01273 257 755 or email info@groundsure.com